Eulogy Of The Homs

Hominy Louise Brigman, a proper southern lady, allegedly.

Hominy Louise was born on April 19, 2013, in Bradley, SC. A town with a population of 170, which means you could fit everyone in town into a single Charleston brunch spot. She passed on November 8, 2024, at 2:21 PM, surrounded by her people, full of ice cream and hot dogs and love. Between those two dates is eleven years, six months, and twenty days, which covers the amount of time Hominy was with us, but it would take twice that, at least, to tell her story.

But let me try, because she wasn’t just a dog. She was The Homs.

She was born at JaBo Kennels out there in the heat and pines and red dirt, with a Golden Retriever for a mother and a Brittany Spaniel for a father. By genetics she was half and half, but by presence she was something like all dog, all heart, all personality, all the time. Her mix of Golden Retriever and Brittany Spaniel made her what folks called a “Gritt,” and grits come from hominy corn. So of course, the new pup had to share her name with the stuff that makes one of the South’s greatest joys. We named her Hominy. And since a proper Southern lady always has a double name, you can say in full when she’s in trouble or being spoiled, she was, officially, Hominy Louise.

We brought her home on June 1st, 2013. “Brought her home” makes it sound so calm. The truth is that Allison and I showed up thinking we were going to meet some puppies and make a level-headed decision like adults, and instead this small, golden-speckled cannonball came blasting out of the pen and into our lives with no discussion. There was no evaluation period. There was no interview. There was only Hominy, who entered every new space like a wrecking ball launched from a larger wrecking ball, and the immediate understanding that she was ours. I watched Allison meet her and fall in love in real time. It wasn’t subtle. It was like watching a circuit close: click. Oh. This is our dog. And that was that. We loaded Hominy Louise up and pointed her toward Charleston, because, and I say this with love to Bradley, this girl was not built for small-town anonymity. She was built to be known.

Hominy had a streak in her from the very beginning that can only be described as “ethically flexible.” For her entire life we joked, “She can’t be trusted,” and we said it so often that it basically turned into one of her official titles. “This is my dog, Hominy Louise, a proper Southern lady who cannot be trusted.” But I want to be clear about what that means, because it’s part of her soul. She was never mean. She wasn’t destructive just to watch the world burn. She was simply opportunistic in a way that bordered on strategic genius. If you made the mistake of leaving a plate unattended, even for a few seconds, The Homs considered that an act of surrender. You looked away and, by the ancient laws of dogs, you had clearly abandoned the meal, and it was now salvage. If you didn’t quite push the trash lid down all the way, well, now that wasn’t “trash,” that was “foraging,” and she was, frankly, contributing to the household. And she wasn’t reckless about it. She would wait. She would watch you. She wouldn’t go for the pizza crust while you were looking. She’d wait for you to stand up to grab a drink, and then she’d strike with military precision. It was theft, yes. But it was respectful theft. Elegant, even.

The early years blur in my memory in the way that the happy parts of your twenties blur. We were in a little townhome off the West Ashley Greenway then, back when money was tight and the furniture was a mix of “found,” “borrowed,” and “don’t lean too hard on that.” Sunday night was Game of Thrones night. We’d order pizza, and everyone got a slice, including Hominy, who patiently, and I cannot overstate how intensely she could “wait patiently”, sat for her pizza crusts. We called them “pizza bones,” partially as a joke and partially because “pizza bones for the good girl” just felt right. These were also the years when she learned me and Allison like a map. Allison was in law school and living under that kind of constant academic strain that makes the whole house feel like it’s holding its breath, and during those stretches when she had to bury herself in studying, it would often just be me and The Homs. We’d go for walks. We’d go for aimless car rides. We’d fall asleep on the couch with the TV still on. She turned “just being in the room together” into its own kind of safety.

We eventually moved from the townhome to a little house on 5th Ave in West Ashley, and that became another Hominy era completely. There was a dog park in walking distance, which to Hominy was like saying, “There’s a festival in walking distance, and everyone at the festival is already in love with you.” Hominy never met anyone who wasn’t, in her mind, destined to be her new best friend. She gave out friendship like people give out business cards. Other dogs, strangers, kids, mail carriers, whoever — she loved them first and asked questions never. She also discovered the skate park there, and would run the fence absolutely convinced that every single skateboarder had come to meet her specifically. She’d sprint back and forth, tail up like a flag, doing this excited bark that sounded less like “Warning!” and more like “HELLO!!! HELLO DO YOU SEE ME I AM VERY GOOD AND AVAILABLE FOR PETS.” And if they didn’t come over immediately to adore her, she looked personally offended, like, excuse me, sir, I watched you do a kickflip, the least you can do is acknowledge greatness in return.

Life, because it’s life, kept changing. Allison graduated law school. We added another dog, Maple — or, more honestly, Maple added herself, the way certain dogs just materialize in your home one day like, “Hi. I live here now. This is non-negotiable.” Hominy loved having another dog in the house. It made her feel like captain of a team. But for me and Allison, things got harder. There are breakups that are dramatic and explosive, and then there are the quiet kinds that hurt in a deeper way because you can feel both of you trying so hard and still not making it work. We made the choice to split. It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t clean. But in the middle of all that, Allison did something I will always be grateful for. She knew how much time Hominy and I had logged together — all those nights during law school where it was just me and The Homs figuring it out — and she let Hominy stay with me.

That decision was not small. That was an act of love, too.

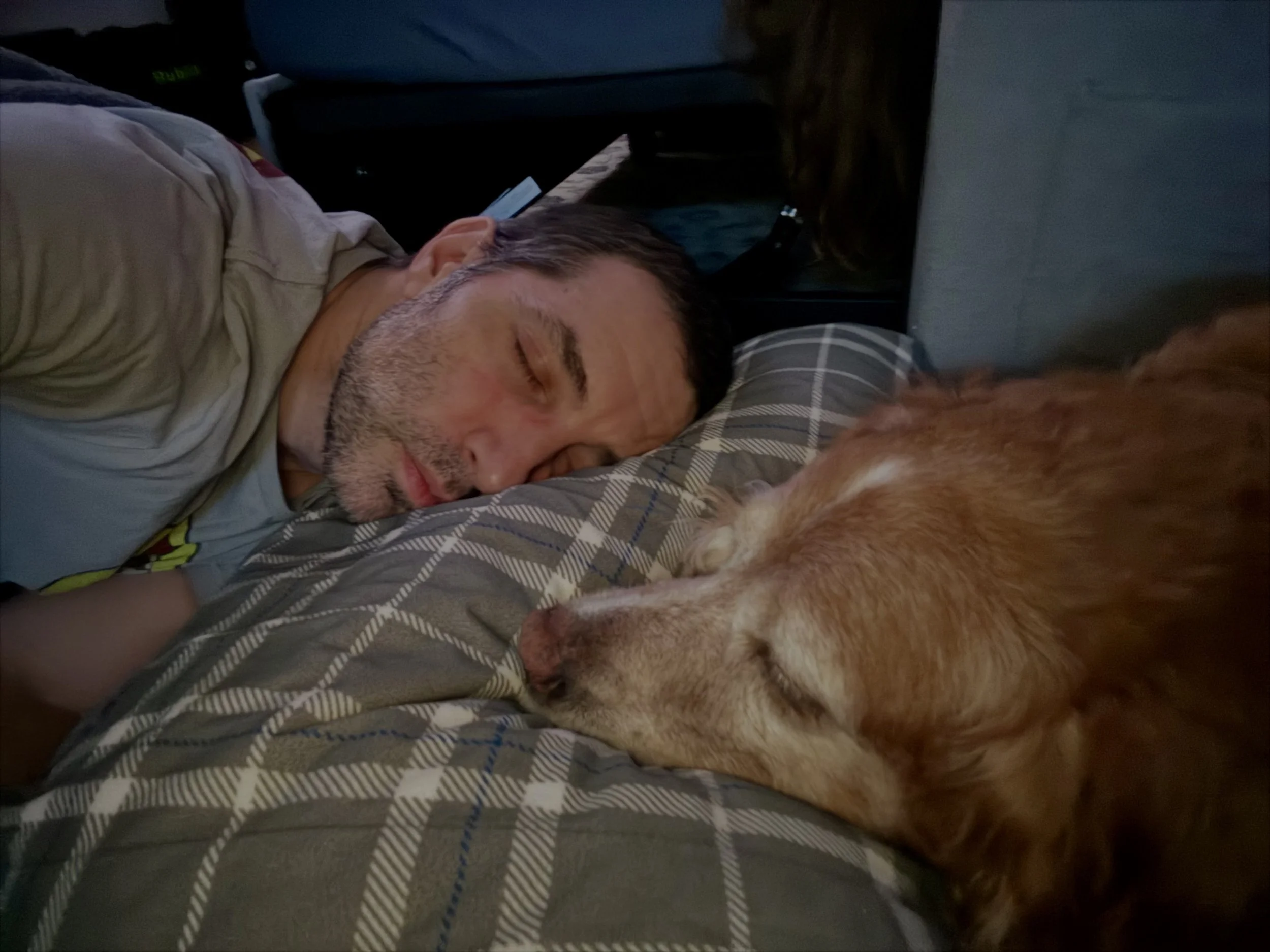

I moved out to James Island with my friend Jeff. If you’ve ever gone through heartbreak plus relocation plus “Who am I now?” all at once, you know that it’s a very specific kind of lonely. There’s a silence to it. It’s the kind of silence where you can hear the refrigerator hum and it sounds like judgment. That period of my life was heavy and isolated in a way that I still don’t totally like thinking about. But I was never actually alone, because wherever I was in that house, Hominy was there too. Every night she curled up with me, not near me, not at the foot of the bed like some dogs do, but against me. Weight and warmth and heartbeat. It’s hard to explain how much that matters unless you’ve needed it. During the day she had Jeff’s huge backyard — this wild, tall-grass, field-of-smells situation that she treated like her personal research lab. Nose down, tail up, patrolling her kingdom. And then there was Folly Beach. We were so close to Folly that beach walks and swims became a routine. Salt air, ocean wind, paws in the surf. There are pictures of her at the beach from that time, that slightly older dog who still looks lit from the inside, and you can’t see it from just looking at me in those photos, but I’ll tell you the truth: in those years, that dog felt like the center of my universe. She wasn’t just my best friend. She felt like the one steady point I could grab with both hands.

Time, rude as ever, kept moving, even when I didn’t. Eventually, I met Elizabeth. The way movies tell it, you meet Someone and there’s instant violins and the lighting changes. Real life is slower and honestly better. We started spending time together. We started building pieces of a shared life in that gentle way where suddenly you realize, “Oh. We’re an us.” At first, Elizabeth was skeptical of The Homs. And let’s be extremely fair here: that was reasonable. Hominy had a long, well-documented record of, quote, “cannot be trusted,” particularly around unattended plates, and Elizabeth was not thrilled to walk back into the room and discover that a highly meaningful portion of her dinner had simply… vanished, leaving behind only a dog who was licking her face like, “I believe this has been a delightful evening for both of us.” But here is an immutable law of physics: you do not resist Hominy Louise forever. You can’t. Nose boop by nose boop, nap by nap, snuggle by snuggle on the couch, The Homs wore her down. They became a duo. Hours together on the sofa became normal. Sometimes at night, Hominy would stay with Elizabeth until she fell asleep and then climb the stairs later to crash against me. Other nights I’d have to bribe Hominy to come upstairs at all, and even then I could feel her thinking, “Fine, but only because you have treats and also you’re warm.” Somewhere in all of that, our strange little constellation solidified into a family.

And then there were the kids. Hominy never had pups of her own, but that doesn’t mean she wasn’t a mama. Enter Wyatt and Charlotte. By then she’d started to gray around the face, that lovely sugar-white frosting that older Golden mixes get. Her famous “cannonball down the stairs because it’s breakfast time do not delay” had slowed into a trot, and then into a careful, joint-conscious walk. But the instant those kids showed up, all the years went out of her joints. She would play tug. She would flop in the grass. She would roll belly-up in total surrender joy. You could see her choose energy for them. Dogs know which humans matter. They just do. She knew: these are my kids.

But here is one of the most unfair things about loving a dog: they live on fast-forward. For us, a “few years” is the middle. For them, it’s an era. You can feel it, if you’re paying attention, when you’re exiting one era and entering the next. One day at West Ashley Veterinary Clinic, during what should have been a normal, boring check-up, we felt some lumps on our plump little Gritt. We had them looked at. We met with Dr. Badger; Let me pause here and say that if you are lucky in this life, you will get a vet like Dr. Badger, someone who doesn’t just care about “a dog,” but cares about your dog, sees your dog, calls her by her name. The tests came back and they were not good. The tumors were real, and they were not the kind you ignore and hope for the best. We all understood, even if we didn’t say it right away: we were in the twilight now.

People talk about “twilight” like it’s a short fade-out, like a movie rolling credits. That’s not how it works. Twilight can last a long time. Hominy lived for years past that diagnosis. Years. She slowed down, yes. She got deliberate. She aged in that very dignified way where her face went white and her eyes went softer and wiser, and every step down the stairs became a careful conversation with gravity. Pillows stopped being optional and started being a medical requirement. But that spark — that internal, defiant joy — never went out.

Those years weren’t without fear. At one point, we left Hominy with a Rover sitter, and the sitter didn’t take the level of care you have to take with an older dog who is, let’s be honest, sneaky. Hominy got into the trash. Normally that’s a “ugh, you little thief” situation. At eleven years old with tumors, it was not funny. She ate things she absolutely shouldn’t have, and it turned into an emergency. She needed surgery. It was bad enough that we really thought we might lose her then. I still don’t fully like remembering that. But the thing is: The Homs was a Gritt, and she showed real grit and a stubbornness to keep going. Between that stubborn will and some incredible veterinary care, she clawed her way back to us. She wasn’t quite the same physically afterward, recovery at that age takes something out of you forever, but she came home. She came back. She gave us more time. She always gave us more time.

In the last stretch, you could see how hard everything was for her, even in the small everyday acts. Going upstairs was now a two-part mission. She’d pause on the landing halfway, catch her breath, then finish. Going down took full attention, like going down a ladder instead of stairs. If she got too excited, she’d start coughing, these rough little fits that scared me because you could see how much effort it took her to calm back down. The body that had carried her at full sprint across dog parks and down beaches and into every room of my life was getting tired. She was still herself, still loving, still wanting to be with us, still looking for food opportunities like a plump, geriatric criminal mastermind. But she was tired.

So we did the last and hardest thing you ever have to do for a dog you love. We chose mercy.

We went back to West Ashley Veterinary, and I sat with her and talked with Dr. Badger, and we said the quiet parts out loud. We talked about her pain, and her breathing, and her dignity, and what “comfortable” really means at the end and who the decision is for. And all of us — me, the vet, and honestly Hominy herself, who had this look I will never forget — understood that it was time.

On her last day, we did it right. I called Allison, because Hominy was never just mine. She will always be ours. We planned one last celebration with Wyatt and Charlotte, because if you ask me, that’s who she’d have chosen if she could talk. We took her to Ye Ole Fashioned Ice Cream, and we let her have everything. Ice cream. Hot dogs. The works. Full permission to indulge. No “only a little bit” voice. Just joy. Just yes. She got to feel like the center of the universe, which, to be fair, she always assumed she was.

And then, on November 8th, 2024, at 2:21 PM, with a full belly and surrounded by her people, wrapped up in love and hands and soft voices telling her she is such a good girl, the best girl, our girl, Hominy Louise went to sleep and crossed the rainbow bridge.

The house feels different now. Grief is strange because it makes the world both louder and quieter at the same time. I still, to this day, see her out of the corner of my eye sometimes. I still pause before I set down a plate on the coffee table. I still expect to hear her nails on the stairs at night. There is not a single day that I don’t think about her. That’s not poetic exaggeration. That’s just neurological reality at this point. I have thousands, literally thousands, of photos of her from puppyhood to her white-muzzle years, because I am the kind of person who can’t help but try to trap time in pixels. If you look through them in order, you can watch her age. But you can also watch us grow around her. You can watch our entire family change shape: different houses, different jobs, different stages of love, heartbreak, repair, and joy. In every version of my life, in every configuration of “home” I’ve ever had, she’s right there in the frame. She is how I measure eras. “That was during the Hominy years” is a complete timestamp in my head.

In a world full of “good girls,” she was the best. She was joyful and stubborn and ridiculous and soft. She was gentle with kids and shameless around unattended dinner. She was a proper Southern lady who absolutely could not be trusted. She made the house feel alive just by being in it. People say dogs are loyal like it’s just a trait. It isn’t. It’s a promise. A dog steps into your life and says, without paperwork or ceremony, “I’m yours. That’s my whole plan.” If you’ve ever had a dog truly bond to you, you know that look. The look that says, “You and me, that’s the deal.” I got that look for eleven years. I will spend the rest of my life trying to deserve it.

She saved me in a hundred private ways. When the rest of my life fell apart, she didn’t. When I didn’t know who I was anymore, she already knew. “You’re mine,” she said, just by lying against my legs and refusing to move. There is something almost unfair about how completely a dog will love you. They ask for nothing higher than the privilege of being your best friend.

In the end, when breathing was work and stairs were hard and the spark in her body was dimmer than the light in her eyes, she trusted me to do the hardest thing. She trusted me to love her enough to let her rest. I would have carried her forever if wanting it hard enough could have made that fair. But love, real love, sometimes means being the one who says, “You can rest now. You don’t have to be tough anymore. I’ll take it from here.”

By the time you, dear reader, get this post it will have been a year sense Hominy has been gone, and she’s also not gone at all. She’s in the way I still check that the trash can lid is really, actually closed. She’s in the pause before I leave a plate on the coffee table. She’s in the automatic way I still look for her at the foot of the bed in the dark. If love leaves an imprint, then my whole life has her paw marks in it.

Rest easy, Hominy Louise. You were, and are, so loved. I was yours. You were mine. That was the deal.